In a week in which neutrality regulation is making a lot of news, I hope that Robert Hahn and Hal Singer's terrific new study, "Why the iPhone Won't Last Forever and What the Government Should Do to Promote its Successor" gets some attention. It provides a wonderful overview of how dynamically competitive the mobile marketplace has been over the past two decades and why critics are wrong to get worked up about the short-term "dominance" of Apple's iPhone. Here's the abstract of their paper:

Because of the overwhelming, positive response to the iPhone as compared to other smart phones, exclusive agreements between handset makers and wireless carriers have come under increasing scrutiny by regulators and lawmakers. In this paper, we document the myriad revolutions that have occurred in the mobile handset market over the past twenty years. Although casual observers have often claimed that a particular innovation was here to stay, they commonly are proven wrong by unforeseen developments in this fast-changing marketplace. We argue that exclusive agreements can play an important role in helping to ensure that another must-have device will soon come along that will supplant the iPhone, and generate large benefits for consumers. These agreements, which encourage risk taking, increase choice, and frequently lower prices, should be applauded by the government. In contrast, government regulation that would require forced sharing of a successful break-through technology is likely to stifle innovation and hurt consumer welfare.

"New technologies often seemingly emerge from nowhere, but also frequently lose their luster quickly," Hahn and Singer go on to argue. As evidence they cite the recent examples of Second Life and MySpace, which were hyped as potentially become dominant providers in their respective areas just a few years ago, but now are subjected to intense competition. "[T]he the mobile handset market is subject to these same disruptive forces," they argue:

an iconic handset emerges, is quickly crowned the "winner," and soon thereafter is replaced by another technology that was not even conceived of at the time the "winner" was launched. Many iPhone-inspired smartphones, including the Blackberry Storm and the HTC G1, could unseat the iPhone in the smartphone segment. We argue that heavy-handed regulation of such dynamic markets is likely to reduce welfare on net. The cost of erring through regulatory intervention--for example, by restricting voluntary private agreements that promote risk taking--can be significant. Delaying the benefits associated with innovation in mobile handsets could cost consumers dearly. In sum, exclusive contracts between handset makers and wireless carriers benefit consumers by encouraging innovation by both handset makers and wireless service providers that are vying for market share, and by enabling some handset makers to remain viable. These benefits take the form of greater variety of choices in handsets, greatly enhanced capabilities, and a more affordable range of device options. Banning exclusive contracts could have the unintended consequence of reducing innovation, reducing options, raising prices, and potentially establishing market dominance for an incumbent handset maker.

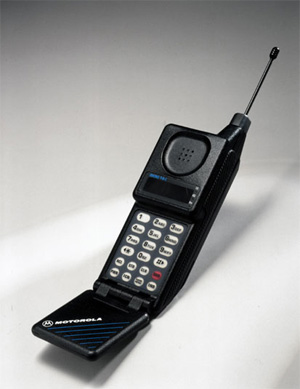

In their excellent history of handset innovation over the past two decades, Hahn and Singer point out that there were many other "iconic" phones that some felt represented the end of the road in terms of innovation. I just love this quote they unearthed from a 1989 Fortune article about how the release of Motorola's MicroTAC flip phone represented the apparent pinnacle of handset innovation: "Portable phones won't get a lot smaller than this one. After all, they have to reach from your ear to your mouth."

This highlights the myopia that sometimes accompanies technological forecasting and public policymaking. We sometimes just can't think "outside the box" and comprehend the ways in which technological devices or services might come along and leapfrog today's market leaders. It gets back to the point I made in my recent book review of Gary Reback's over-the-top ode to antitrust regulation, Free the Market: Those who view markets through the lens of the a static competition, fixed-pie mentality always seem to live in fear of short term "market power" while those of us who believe in dynamic competition see markets in a constant state of flux and expect that sub-optimal market developments or configurations are exactly the spark that incentivizes new form of market entry, innovation, price competition, and so on. And the real problem with that static competition mentality is that it often leads to knee-jerk regulatory responses. Here's how I put it in my recent debate with Larry Lessig:

What concerns me about the way Prof. Lessig approaches these issues in Code and in his subsequent work is that he is far too quick to declare the debate over by labeling short-term.. hiccups as sky-is-falling market failures. The end result of such myopic techno-pessimism is the inevitable call for governments to intervene and "do something" to correct supposed [market] failures.

In other words, have a little faith and some patience. Apple's iPhone is today's hottest handset, but it's hardly the end of innovation in this marketplace. And we certainly don't need handset regulation or "device neutrality" as a solution to this non-problem. Read Hahn and Singer's dynamite new paper for a better understanding of why that's the case.