Regular readers will know that Adam and I have been waging a lonely defensive action in the war on "Free!" (ad-supported) content and services online, pointing out that restrictions on data collection and use for advertising would ultimately hurt consumers by reducing funding for the sites they love (1, 2, 3, 4). In short, there is no free lunch! I've also written a number of posts this past week about the dangers inherent in antitrust regulation--arguing that government efforts to make online markets more competitive through antitrust tinkering generally do more harm than good (1, 2, 3).

These two debates have long shared a common thread: Some have argued that effects on privacy should become a part of antitrust analysis and those who consider Google to be "Big Brother" want Washington both to clamp down on data use ("baseline privacy legislation") and to ramp up antitrust scrutiny of the company.

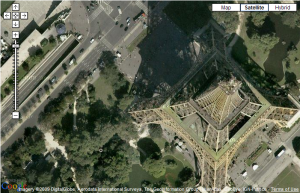

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on "Free." Bottin Cartographes has sued Google for unfair competition (concurrence déloyale--literally, disloyal competition) and abuse of its market dominance. The case is a little more complicated than English language reports suggest: It's not just that Google is giving away a product (Google Maps) that Bottin charges, or wanted to charge, for. Like Google, Bottin charges enterprise users. But Bottin complains that Google doesn't show ads on the public version of Google Maps. (Neither does Bottin, but maybe that's part of why they're upset.) Bottin's lawyer claims that Google's "strategy is to capture the market and squeeze out the competition by creating a monopoly for itself." He goes on to assert that Google is "ruining the market" for mapping services.

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on "Free." Bottin Cartographes has sued Google for unfair competition (concurrence déloyale--literally, disloyal competition) and abuse of its market dominance. The case is a little more complicated than English language reports suggest: It's not just that Google is giving away a product (Google Maps) that Bottin charges, or wanted to charge, for. Like Google, Bottin charges enterprise users. But Bottin complains that Google doesn't show ads on the public version of Google Maps. (Neither does Bottin, but maybe that's part of why they're upset.) Bottin's lawyer claims that Google's "strategy is to capture the market and squeeze out the competition by creating a monopoly for itself." He goes on to assert that Google is "ruining the market" for mapping services.

Bottin seeks half a million Euros (plus interest) in damages, but their lawyer insists: "It's not a question of money. Either Google puts advertising on Google Maps or the company must be forced to pay damages and abide by the terms of fair competition." The hearing is set for October 16.

This argument, crazy as it sounds, is one Google is likely going to have to fend off repeatedly in the coming years--and not just in Europe, where "unfair competition" is still very much about protecting competitors rather than consumers. Chris Anderson, author of the new book Free, recently addressed this very issue. Anderson's book describes multiple ways of supporting "Free" content and services.

This use of Free is part of [Google's] "max strategy" -- it uses Free to get its products in the hands of the greatest number of users, and then figures out some way to get money from them (mostly with ads, but sometimes with "pro" versions of the services, in which users can pay for more storage or features, using the "freemium" business model).Google does, indeed, charge for an Enterprise version of Google Maps, while giving away the basic version for free with no ads. Anderson puts his finger on why this might seem problematic to some:

In response, Google's Dana Wagner pointed out thatGoogle can give away so much because the incremental cost of serving one more Web page to one more user is almost nothing -- and falling as technology gets cheaper. This is the difference between the "bits economy" and the "atoms economy." The marginal cost of production for digital things is so low that Free becomes not just a marketing gimmick but the default price in most markets, driven by economic forces as real online as gravity is in the real world.

But companies still have to make money, so there are limits to how much they can provide free. Not a problem for Google. Its core advertising business is so powerful, dominant and profitable that it can subsidize almost everything else the company does, using Free to get customers in new markets.

Is that fair, when so many of its competitors don't have a similar golden goose at the core of their operations?

- "almost no one believes that Google would or could start charging exorbitant prices for products like search and Gmail"--for the very same reasons that everyone else gives these services away: It's very difficult to charge anything for digital goods and services whose marginal cost is effectively zero.

- "competition laws are concerned with what's best for consumers, not for competing companies, and there's little doubt that from a consumer perspective, free products are usually a great thing."

And even if Google weren't charging anyone for Google Maps and really were just cross-subsidizing it from other revenues, why would that be bad? This may well be what's going on right now with Google Docs, which has no ads ads and isn't upsold in a Freemium model. As Anderson said of Google Docs:

Microsoft, meanwhile, is doing just the opposite: using the profits from its dominance of word processors and spreadsheets (Microsoft Office) to subsidize its competition with Google in search (Microsoft Bing). In each case, the companies are using a highly profitable paid product to make another product free, on the hopes of gaining market share by taking price off the table.

Dana's reply is dead-on:

Rather than exemplifying a competitive problem, Chris's example makes the point that in fact there is robust competition, between two companies pursuing similar strategies to win over users from each other. That's competition in action!

The same could be said of Google Earth and Microsoft's Virtual Earth, neither of which is ad-supported or upsold, as well as many of the free services Google offers, such as Goog-411, Google Desktop and Google Scholar. Maybe Google will figure out a way to make money from these services directly. But even if it doesn't, as Ryan has asked, what's the harm to consumers?

Vive la Free!