A recent paper by Tim Wu discusses "Wireless Net Neutrality." He suggests that several features of the U.S. wireless industry may be harming consumers. Overall, he wants wireless carriers to open their networks in many ways. He advocates creating standards that will make it easier for developers to write applications and for hardware firms to create devices that will operate on a network, and following some "net neutrality" standard for use of the spectrum itself.

It is an interesting paper, but is flawed in several fundamental respects.

First, Wu writes as if this were a new issue. Just like the broader debate over network neutrality, this is simply another version of an extensively debated topic: when should a network operator be forced to allow users particular types of access to its network? Wu ignores the history of this type of regulation.

We saw such regulations in the U.S. under the UNE-P regime, when the telcos were forced to sell access to their networks to competitors at regulated rates. Proponents had hoped that unbundling would have a "stepping stone" effect by allowing competitors to enter the market and then, once they had a customer base, would begin to invest in facilities. Unfortunately, it did not turn out that way. Few of the CLECs, as they were called, invested in any facilities, while the sharing regulations reduced investment incentives by the telcos. Today, the unbundling debate is largely over in the U.S., though it continues in Europe and elsewhere with respect to broadband access.

Regulating how wireless carriers allow their networks to be used would represent another version of regulating network access, and the history of such regulation does not bode well for its impacts.

This brings us to the second problem. Even in the case of the UNE regime and today's debates in Europe and Asia about unbundling, there is an underlying assumption that some firm had enough market power to profitably act anticompetitively. The wireless industry displays no evidence of any market failure. Thus, even if one believed that sometimes regulating network access had the potential to improve competition, the lack of a market failure in the wireless industry suggests that such regulation would be completely unwarranted in this case.

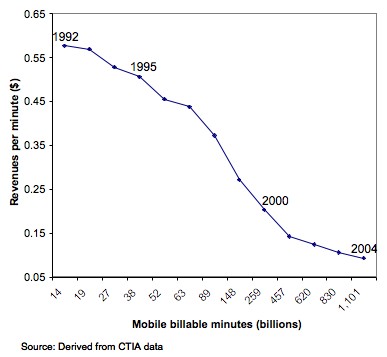

Indeed, the evidence suggests that the wireless market is competitive and has brought tremendous benefits to consumers. The figure below for example, shows that prices have, on average, decreased substantially while mobile use has soared. Wu notes that entering the market takes a lot of capital, but that does not by itself indicate a market failure. The presence of four major national carriers and several regional players (some of which have now bought enough spectrum to eventually provide nationwide service) suggests that investors are able to mobilize resources to enter the market.

Given the unimpressive history of network sharing regulations, one should take care in imposing similar regulations under any circumstances. Imposing them in such a competitive industry makes little sense. Regulating a competitive market is likely to distort investment incentives and ultimately harm consumers.

Nevertheless, it is worth evaluating a few of Wu's specific points.

Wu is concerned by the carriers' controls over the type of devices that can use their networks. He asserts that consumers would be better off if the providers' networks were open to any device manufactured to be compatible with the network technology, including allowing consumers to purchase handsets of their choice rather than the ones approved by the wireless carrier.

Wu compares current restrictions to the bad old days when AT&T the monopolist refused to allow any "foreign devices" to connect to its network because, it claimed, such devices might damage its network. This claim reached its peak of absurdity when AT&T tried to ban the hush-a-phone - a plastic device that snapped onto the telephone's mouthpiece to block out background noise.

AT&T's network attachment rules seemed to be largely intended to protect its monopoly rather than its network. However, comparing the pure monopoly of Ma Bell to today's competitive wireless industry makes for a flawed analogy.

As Wu seems to understand, the current situation may result, in part, from a lack of standards. Indeed, one of his recommendations is for the industry to "work together to create clear and unified standards to which developers can work."

The challenge of creating standards is far more complicated than Wu admits. Standards can be important to an industry, but it is not always obvious how to establish them. Allowing all the firms in an industry to work together to create standards can create large benefits, but also might undercut competition and promote collusion. Some cooperation among firms is important, which is why Congress passed the National Cooperative Research and Production Act in 1993 to allow firms to collaborate on certain research ventures with some protection from antitrust prosecution.

Moreover, it's not at all clear that Wu himself would be satisfied with such a standard. For example, he decries the industry-created WAP standard for viewing web pages. The point here is not to praise or criticize WAP, but to point out that standards are difficult to create, and that Wu was not happy with one standard created under the type of system he seems to now advocate.

Creating standards, especially in high-tech industries that involves a large number of firms, is complicated and there is no single right way. Wu demands that the industry overcome this problem, but it's an issue over which companies and researchers constantly struggle.

Wu is also concerned about the common industry practice of wireless carriers controlling which phones will be able to operate on their networks. Wu asks, "Why can't you just buy a cell phone and use it on any network, like a normal phone?" Part of the answer is that "you can." As he notes, GSM networks (T-Mobile and AT&T in the U.S.) will accept any GSM-compatible phone that is built to operate on the correct frequency. Amazon has a page explaining how to use unlocked GSM phones and seems to offer 163 different phones for this purpose. It would be interesting to know whether the ability to purchase unlocked phones is one of the reasons some customers are attracted to T-Mobile's and AT&T's networks. Another part of the answer is that the standard practice here is for carriers to subsidize handsets to induce people to sign contracts. Would some people prefer to buy unsubsidized handsets and not sign contracts? How many, and how much would they be willing to pay? Do these subsidies increase demand for handsets? If so, how does this increased demand affect innovation? Perhaps knowing something about consumers that choose to buy their own handsets versus those who buy directly from the network operator would shed some light on that question. Unfortunately, Wu seems to already have decided his preferred answer to questions such as these.

Some of Wu's claims may have merit. For example, he is concerned that some advertising may mislead consumers into thinking that they are purchasing unlimited access to a carrier’s 3G network when, in fact, their total monthly allowed use is typically capped.

Overall, though, the wireless industry is robustly competitive and exhibits no evidence of a market failure. Consumers consistently benefit from lower prices and more features. This competition shows no signs of letting up. To ensure that competition and innovation continues in this market, the FCC should continue to move spectrum into the market quickly and make its use flexible and allow it to be traded. The recent AWS auction and the upcoming 700 Mhz auctions are big steps in the right direction. More spectrum will ensure that existing wireless carriers can improve their services and new firms will be able to enter the market.

Regulations always must be considered carefully to ensure that they carefully target a specific market failure and that the benefits of the regulation are expected to exceed its costs. In the case of the wireless industry, there is no evidence of a market failure, and regulations - especially sweeping ones of the type Wu would like us to consider - are likely to impose significant costs on society and ultimately harm consumers.