By Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka

Progress & Freedom Foundation Progress Snapshot No. 6.5, Feb 2010 [.pdf]

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we're busy finishing up a paper with the working title: "The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture." Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we're busy finishing up a paper with the working title: "The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture." Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

This regulatory tsunami could not come at a worse time, of course, since an attack on advertising is tantamount to an attack on media itself, and media is at a critical point of technological change. As we have pointed out repeatedly, the vast majority of media and content in this country is supported by commercial advertising in one way or another-particularly in the era of "free" content and services.[1]

An Attack on Advertising Will Hurt Consumers

But there's a more important reason to fear Washington's new war on advertising: It will hurt consumer welfare. That's because advertising provides important information and signals to consumers about goods and services that are competing for their attention and business--and that scarcest of all things in the modern world, consumers' attention.

Thus, advertising helps solve an otherwise intractable information problem that would otherwise go unsolved without advertising's claims and counter-claims about competing goods and services. Indeed, truthful advertising is itself an important type of speech that communicates relevant information to the public. As Nobel laureate economist George Stigler pointed out in his now legendary 1961 article on the economics of information, advertising is "an immensely powerful instrument for the elimination of ignorance-comparable in force to the use of the book instead of the oral discourse to communicate knowledge."[2] As leading advertising scholar John Calfee has argued, "advertising has an unsuspected power to improve consumer welfare" since it "is an efficient and sometimes irreplaceable mechanism for bringing consumers information that would otherwise languish on the sidelines."[3] More importantly, Calfee argues:

Advertising's promise of more and better information also generates ripple effects in the market. These include enhanced incentives to create new information and develop better products. Theoretical and empirical research has demonstrated what generations of astute observers had known intuitively, that markets with advertising are far superior to markets without advertising.[4]

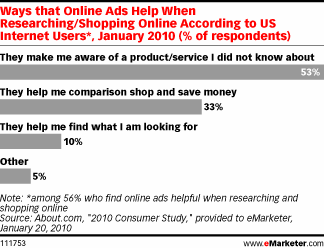

In other words, advertising educates. It ensures consumers are better informed about the world around them, and not just for the good or service being advertised. Advertising also raises general awareness about new classes or categories of goods and services. It helps citizens in their capacity as consumers to become better aware of the options and their disposal and the relative merits of those choices. For example, a new survey by About.com found that "While one-third of the online buyers who were aided by ads said they helped them save money, the majority appreciated online ads for informing them about a product or service previously unknown."[5]

If anything, these numbers understate the vital importance of advertising to consumers, since advertising is so ubiquitous in our capitalist world, it is like the air we all breathe: We rarely notice it except when it annoys or bothers us. Given how deeply ingrained our cultural bias against advertising, and how subtly advertising works to benefit consumers, it's remarkable that so many consumers realize that advertising empowers them by increasing total awareness of the many choices available in the marketplace.

Commercial Speech Is Speech and Deserving of First Amendment Protection

For these reasons, the Supreme Court has made it clear commercial speech is deserving of First Amendment protection like other forms of speech. In a series of key decisions over the past four decades, the Court has highlighted the important role that advertising and marketing plays in facilitating the flow of information that is beneficial to society. As Calfee notes:

Constitutional protection for advertising is explicitly based upon the idea that freedom to advertise brings benefits to markets generally, especially consumers. The central argument in Supreme Court decisions overturning restrictions on advertising is that consumers can benefit from a free exchange of information- the 'marketplace of ideas' celebrated by authors and jurists since at least the time of John Milton.[6]

"Both the individual consumer and society in general may have strong interests in the free flow of commercial information," the Court noted in its landmark 1976 decision in Va. Pharmacy Bd. v. Va. Consumer Council.[7] "As to the particular consumer's interest in the free flow of commercial information, that interest may be as keen, if not keener by far, than his interest in the day's most urgent political debate," Justice Blackmun stressed in that decision.[8] Thus, the Court concluded:

Advertising, however tasteless and excessive it sometimes may seem, is nonetheless dissemination of information as to who is producing and selling what product, for what reason, and at what price. So long as we preserve a predominantly free enterprise economy, the allocation of our resources in large measure will be made through numerous private economic decisions. It is a matter of public interest that those decisions, in the aggregate, be intelligent and well informed. To this end, the free flow of commercial information is indispensable.[9]

The Court's reasoning in its recent commercial speech jurisprudence, notes Media Institute scholar Richard T. Kaplar, can be summarized with the following syllogism:

Economic concerns are as important to our society are as important as political concerns. By extension, economic information is as important as political information. Political information receives full First Amendment protection. Therefore, economic information should receive full First Amendment protection.[10]

Kaplar continued: "Truthful speech about lawful products and services deserve full First Amendment protection. This is a simple proposition, but its implications for freedom of speech extend far beyond advertising."[11]

The Benefits of Advertising Reverberate Throughout the Economy

The beneficial effects of increasing commercial speech and information clearly reverberate throughout the economy--even though the big picture is "anything but obvious to consumers."[12] Smarter consumers make smarter choices. They search for better deals. Products and prices become more competitive as a result--even for consumers who don't bargain-hunt. And the cycle repeats endlessly. This is particularly true for new products and services, thus for promoting technological innovation, as Nobel Prize winning Economists Kenneth Arrow and George Stigler noted in their landmark 1990 study of the benefits of advertising.[13] They point to the example of the microwave oven, introduced in 1967:

Amana [Corporation]'s initial advertising of its pioneering microwave oven provided consumers with information on how such ovens work, what they can do, etc. This created consumer demand for the product, which benefited subsequent entrants, such as Litton and Panasonic. Advertising by these later entrants was used to explain the benefits of their particular brands rather than to explain to consumers the functions of a microwave oven: Amana's advertising had already provided general product information and helped create consumer demand for the product.[14]

This process not only brings new products to market, but also helps upstart innovators dethrone the regnant giants of industry, ensuring that competition remains dynamic and fiercely rivalrous--all to the ongoing benefit of consumers.

Conclusion

These are the stakes for consumers in the "New Assault on Advertising," as we'll explain in our forthcoming report. Government already plays a vital role in ensuring that advertising is truthful and not misleading. But as advertising itself evolves to keep pace with technological change, raising new concerns about privacy and the supposed manipulativeness of tailored ads, further regulation will only serve to limit the provision of beneficial information to consumers, potentially retard new product offerings and innovation, dampen price competition, and indirectly punish media operations and content creators who rely on advertising as their lifeblood.

Related PFF Publications

- Chairman Leibowitz's Disconnect on Privacy Regulation & the Future of News, Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka, Progress Snapshot 6.1, Jan. 13, 2010.

- Privacy Trade-Offs: How Further Regulation Could Diminish Consumer Choice, Raise Prices, Quash Digital Innovation & Curtail Free Speech, Berin Szoka, Comments to the Federal Trade Commission at the Exploring Privacy Roundtable, Nov. 10, 2009.

- Regulating Online Advertising: What Will it Mean for Consumers, Culture & Journalism? Berin Szoka, Mark Adams, Howard Beales, Thomas Lenard & Jules Polonetsky, Progress on Point 16.22, Oct. 30, 2009.

- Privacy Polls v. Real-World Trade-Offs, Berin Szoka, Progress Snapshot 5.10, Oct. 8, 2009.

- Targeted Online Advertising: What's the Harm & Where Are We Heading?, Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer, Progress on Point 16.2, Feb. 13, 2009.

- Online Advertising & User Privacy: Principles to Guide the Debate, Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer, Progress Snapshot 4.19, Sept. 2008.

- Comments of The Progress & Freedom Foundation In the Matter of Sponsorship Identification Rules and Embedded Advertising, W. Kenneth Ferree & Adam Thierer, Sept. 19, 2008.

- Freedom of Speech and Information Privacy: The Troubling Implications of a Right to Stop People from Talking About You, Eugene Volokh, Progress on Point 7.15, Oct. 2000.

- A Taxonomy of Online Security and Privacy Threats, Eric Beach & Adam Marcus, Oct. 29, 2009.

[1] See, e.g., Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka, Chairman Leibowitz's Disconnect on Privacy Regulation & the Future of News, Progress Snapshot 6.1, January 2010, www.pff.org/issues-pubs/ps/2010/pdf/ps6.1-Leibowitz-disconnect-on-privacy-and-advertising.pdf.

[2] George Stigler, The Economics of Information, 69 Jour. of Political Economy 213, 220 (June 1961). "Since Nobel laureate George Stigler's 1961 article on the economics of information, economists have increasingly come to recognize that, because it reduces the costs of obtaining information, advertising enhances economic performance," note Howard Beales and Timothy Muris. "[W]hat consumers know about competing alternatives influences their choices. Better information about the options enables consumers to make choices that better serve their interests." J. Howard Beales & Timothy J. Muris, American Enterprise Institute, State and Federal Regulation of National Advertising, 7-8 (1993).

[3] John E. Calfee, Fear of Persuasion: A New Perspective on Advertising and Regulation, 96 (Agora Association, 1997).

[4] Id.

[5] eMarketer.com, Online Ads Help Shoppers Save, Feb. 22, 2010, www.emarketer.com/Article.aspx?R=1007524

[6] Calfee, Id. at 107-8.

[7] Va. Pharmacy Bd. v. Va. Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748, 765 (1976).

[8] Id. at 763.

[9] Id. at 765 (emphasis added)

[10] Richard T. Kaplar, Advertising Rights: The Neglected Freedom (1991) at 60.

[11] Id. at 71.

[12] Calfee at 115.

[13] Kenneth J. Arrow, George J. Stigler, Elisabeth M. Landes & Andrew M. Rosenfield, Economic Analysis of Proposed Changes in the Tax Treatment of Advertising Expenditures, (Lexecon Inc., 1990), available at www.scribd.com/doc/27267813/Economic-Analysis-of-Proposed-Changes-in-the-Tax-Treatment-of-Advertising-Expenditures.

[14] Id. at 16.